From Crisis to Change

GIM International Interviews Willi Zimmermann

Land degradation, violent disputes, resource piracy and misuse of power are just some of the challenges faced by more than forty countries in a world where resources are in scarce supply. When we approached world-renowned land governance expert Willi Zimmermann for this interview he humbly introduced himself as a land surveyor who facilitates the protection of land rights. But Zimmermann has had a long career as a specialist in land management, the process of sustainably managing the use and development of urban and rural land resources. He outlined for us the extent of the current global land predicament.

Could you define land administration for us?

It's the process of determining, recording and disseminating information about the ownership, value and use of land when implementing land-management policies. It determines the land rights of people and provides an institutional and legal framework for land rights. Land resources are used for a variety of purposes that interact and may compete with one another. That's why countries need to plan and manage all uses in an integrated, sustainable manner that matches land rights with land use. Recently the international community has begun to talk about ‘land governance', which is key to the proper management of land resources. It's a view upheld by both the World Bank and the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO).

Why is land administration such a major cause for concern?

Fighting poverty and improving food security for an ever growing global population requires more land for more people. Expansion of food-crop production is possible in only a few countries, such as the Ukraine, Russia, Angola and Argentina. At the same time, enormous additional pressure is being brought to bear by desertification and degradation, water scarcity, the expansion of areas used to grow animal feed, the need for bio-fuels and, of course, big speculative land deals on the part of international investors; all factors that have led to a decrease in the amount of land available per head. According to the FAO there are over one billion people living in absolute poverty, which is directly linked to land rights. And the alarming fact is that more and more people are losing their claims in Africa, Latin America and Asia, where land rights are precarious.

Can you describe the background to this situation?

There is a great divide between countries which have a long tradition of land rights and those which have none. More than half of the 196 countries around the globe came into existence only in the last fifty years. Many non-member nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have no prerequisites for sustainable land management based on legal principles. About a hundred of these countries have no functioning land-administration system. It is therefore hardly surprising that individual well-intentioned development co-operation tools, standards and procedures often fail to achieve the desired effect.

The impact of political instability and conflict on land is enormous and includes floods of refugees, land degradation, land-mine contamination, violent land disputes, resource piracy and misuse of power. Between forty and sixty countries in the world are in this situation. In many African countries land is not registered and power is centralised, so people's long-standing customary rights are ignored by corrupt officials. The point is that, as a resource, land is fundamental to the livelihood of people and for shelter. Take their land away and they have nowhere to live and no means of making a living.

What are the biggest problems arising from the lack of land-administration systems?

Without the security of land rights people can be evicted and land acquired by those in power. This means that no investment takes place, because there is no incentive to develop or add value to land, as it is impossible for people to secure their investment. There are still eighty countries in the world which do not have clearly defined national borders. This means no investment in the border areas and no transparent crossing from one country to another, which is a major security risk.

Can you give us a global overview of the development of land administration?

Ninety percent of land rights in Africa, and 60% globally are not documented. Most problems with land rights exist in countries where the risk of conflict is high, where the political situation is unstable, and where natural disasters are common - all of which leads to large numbers of refugees. Somalia is a case in point. The United States made a mess of Somalia in the ‘90s, and the result provides an example of how national security and land issues are interlinked. Somalia has undergone desertification and drought, coupled with exploitation by international fisheries. In addition, internal conflict between tribal leaders and central government (a problem which has its roots in the colonial era) has destroyed much of the country. As a result, its people are always on the move, with resources constantly decreasing. The situation here highlights how much more careful we should be in dealing with conflict and the resulting land issues.

What needs to be done?

What we need to do is establish a normative framework, collect data, create knowledge, take action, get people involved, measure the impact, learn from the experience, and go back again to the beginning of the process. It's important to organise workshops with all stakeholders and to make available platforms in different countries. The process should not have to start with a national disaster. There are no easy answers, but as a professional community such as FIG or the International Association of Geodesy (IAG) we have to be more proactive and inclusive in getting all countries involved. We have to create enabling forums where members of civil society are made aware of the benefits of land-administration systems. The goal must be to create a normative framework; we cannot bypass governments, but, at the same time, politicians in government who are not working in the best interests of their people should not be allowed to play their own game.

What is the effect on people living in slums?

There are about one billion slum dwellers worldwide; according to UN-Habitat this figure will double to two billion by 2025. Professional surveyors are doing a good job, but they are only achieving about 20% of what needs to be done to move these people step-by-step from an informal to a formal situation. It's an extremely complex issue. People living in informal homes must at least be given the right to stay on that land, if not the right to own it. More than eight million people are forcibly evicted form their homes every year. It's an untenable situation, given that shelter is a basic human right. There is no blueprint for transforming slums into formal settlements, but countries like Brazil and South Africa have done a good job of regularising shack lands.

Could you describe how you helped establish a professional land-management qualification in Cambodia?

As part of my work in reforming the land sector in Cambodia with GTZ, and with the support of the Finnish and Canadian governments and the World Bank, we created the Faculty for Land Management and Administration at the Royal University of Agriculture in Phnom Penh in 2002. In many countries where there is no land-administration system, any start made on setting up a legal and institutional infrastructure must be backed by systematic professional education. To date, 160 students have graduated from the faculty, and all are involved in the sector. A similar effort is underway in Palestine.

Why does it take so long to set up a land-administration system?

It's a very difficult and huge task. We need a new and innovative approach where social science and high-tech come together. It comes back to my point about systematic professional education. We have to build capacity. It's about creating partnerships between local and international universities, providing guest lectures and distance learning opportunities, and building international networks.

How many surveyors are needed globally?

At present there is an unacceptable lack of professional capacity. For example, the seven leading countries with long-standing professional education infrastructures in Africa (Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania, South Africa, Morocco and Egypt) have around 90% of all surveyors on the continent. In, for example, Germany, there are about six times more land surveyors than in the whole of Africa. I believe that the absolute minimum ratio of professional surveyors to people in developing countries should be 1:100,000. In Angola there are no more than ten.

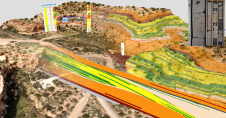

Land administration relies on models; could you elaborate?

There must be a strategy in the geodetic world for fighting the reality of the global geodetic divide. A good model includes the following six elements:

- land governance

- legal and normative framework

- a modern geodetic reference systems

- a coherent spatial data infrastructure

- professional educational infrastructure

- professional associations and networks

By putting these measures in place you can create a system where accountability (and) transparency and professional ethics are in evidence. Professional associations like the FIG are testimony to what can be achieved, but again only about ninety countries in the world are members.

How does one become a policy consultant?

It's not a career that is limited to land surveyors. We need legal expertise, economists, geographers and technologists who are able to develop applications that are easy to use in developing countries. I became involved after working with a group of chiefs in Africa forty years ago to define tribal boundaries and customary land rights. Since then it's been a lifelong learning process.

What about modern developments?

The drive to use modern geo-technologies is ongoing and important. Technology is key, but first we need to develop professionals in the field. Once the professional and institutional capacity is in place you can begin to look at the technologies available. People are still under the illusion that technology is driving the game. But it's not.

Is there a need for standards?

Standards are part of a normative framework. What we need are spatial-data infrastructures, resource assessments, reference systems, land-governance models, educational infrastructures and professional associations. None of these can be created and developed without standards, whether on the technical or the professional side. The Kyoto protocol, WTO, G20 resolutions and the UN conventions are the first steps towards global governance. In addition there have been geodetic contributions for building global governance by providing global public goods such as GNSS, GEOSS, the FAO Voluntary Guidelines for Responsible Management of Land and other Natural Resources, the World Bank Land Governance initiative, the UN-Habitat secure urban tenure initiative, and the TI Global Corruption Barometer 2009, all of which are helping us move in the right direction.

Value staying current with geomatics?

Stay on the map with our expertly curated newsletters.

We provide educational insights, industry updates, and inspiring stories to help you learn, grow, and reach your full potential in your field. Don't miss out - subscribe today and ensure you're always informed, educated, and inspired.

Choose your newsletter(s)