Cartography as a Tool for Supporting Geospatial Decisions

From 25 to 30 August 2013, the 26th International Cartographic Conference is being held in Dresden, Germany, bringing together cartographers and geographic information science specialists from across the globe. In recognition of the importance of the study and practice of mapmaking, GIM International interviewed Ferjan Ormeling, the prominent Dutch cartographer. Covering cartographic challenges, the power of maps, and lessons that can be learned from the past, Ormeling's views are that of an inspired and inspirational proclaimer of his specialist field.

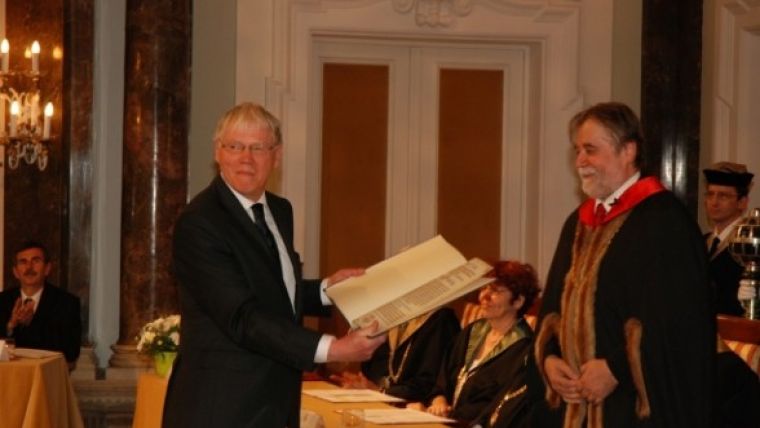

In May 2013 you were awarded a Professor et Doctor Honoris Causa degree in cartography from Eötvös Lorand University (ELTE) in Budapest, Hungary. Congratulations. How did that feel?

Well – and I think this is a standard reaction of most Doctores Honoris Causa – since it came completely out of the blue, my first reaction was astonishment. But I really feel honoured with this distinction. I am proud to have received this title, especially from ELTE. There are very few Doctores Honoris Causa in cartography, so I regard this really as a tribute to the profession. It also shows an academic acceptance of the profession.

Could you tell me a bit more about your career as a cartographer?

When I was a child, my father was director of the Geography Institute for the topographic survey of the Netherlands East Indies. Hence, much of my childhood was spent walking through the premises of that institute, experimenting with the optical pantograph and playing hide and seek between the large cardboard models of volcanoes in the corridor. So as you can see, working with maps came quite naturally to me.

As a student I studied for a degree in geography at Groningen University in The Netherlands. During that time I worked part-time as an assistant atlas editor with Wolters Publishing House. I spent eight years employed by Wolters, working on the Bosatlas.

When I graduated, my initial idea was to land a job as cartographer for an oil company. Cartography was not offered at Groningen so I travelled to Utrecht once a week where professor Koeman lectured in cartography. In Groningen, I also studied Arabic. Armed with this combination, I thought I would be the ideal candidate for Aramco to hire for map production. But things turned out differently: I never realised my idea. Instead, I was hired by Utrecht University to help shape the new cartography education programme, and I have been there ever since.

One of your special interests is the history of cartography. What intrigues you about the past and what can today’s cartographers learn from it?

Well, I’m a recent convert to the history of cartography. Up until I retired, I taught the many different aspects of modern cartography and hardly spent any time on its history because my immediate colleague Günter Schilder was teaching that. Since my retirement, I’ve joined his research group, Explokart, which is now chaired by Peter van der Krogt, and moved with them to Amsterdam University. I think as a cartographer you must know about the past; you can’t be a really good cartographer unless you realise how spatial information was transferred in the past. When you look at old maps, it is clearly apparent that they were really social constructs. It is society that orders maps, and not cartographers themselves – society decides on the contents of maps. This helps to give you a better understanding of spatial information transfer in the present.

Another area of interest is toponymy, the study of place names. What is it about toponymy that fascinates you so much?

Around 1980, I was asked to join a conference about place names in Bozen, in Italian Bolzano. While I was there, I realised that South Tirol had been a German-speaking area for a thousand years. In 1919 the Italian army came in, changed the name signs of the towns and villages – and even tried to the change the citizens’ surnames – and produced maps which made the area look completely different from previously. Even the Italians themselves had produced maps of Southern Tirol before the First World War showing only German names, and then all of a sudden in 1919 they translated all the names, Italianised them, which made the area look completely different on the map. This was an eye-opener for me about the power of maps. Just by manipulating the content, i.e. the names, they made look the area completely Italian. Looked at the new map, the logical reaction would be: ‘Of course this should be a part of Italy, just look at the names!’

Then I used this as the subject of a PhD thesis examining the way national mapping agencies in Western Europe dealt with minority names. I studied the processes through which names from minorities where adapted to the official language. It turned out that in a number of countries, especially in Scandinavia, the authorities were very accommodating to the minorities. That was not the case in most of Central and Southern Europe at that time. Even in The Netherlands, topographers tended to translate names used by the Frisian minority, with some pretty odd mistranslations as a consequence. Things have changed since then, and Frisian names are now used on the map wherever the local authorities want to use them. And presently, thanks to increased interest in cultural heritage, this attitude is accepted all over Europe.

Value staying current with geomatics?

Stay on the map with our expertly curated newsletters.

We provide educational insights, industry updates, and inspiring stories to help you learn, grow, and reach your full potential in your field. Don't miss out - subscribe today and ensure you're always informed, educated, and inspired.

Choose your newsletter(s)