How Big is Global Insecurity of Tenure?

This article was originally published in Geomatics World.

Current sources of Global Land Indicators are limited with only 30% of the globe covered. Robin McLaren believes that new, innovative sources of land information can strengthen our understanding of the size of the global insecurity of tenure gap.

The land sector has not been good at monitoring progress of global initiatives in fighting insecurity of land governance and tenure. But now there is no hiding. Solving land issues is on the radar of the G8 and is reflected in the adopted Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure, Forests and Fisheries (VGGTs). After a successful lobbying campaign, land is integrated into the post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The tenuous nature of our often quoted 70% insecurity of tenure statistic highlights the challenge for the land sector to design and implement global land indicators and monitoring frameworks associated with land governance and land tenure security that are based on feasible data sources and data collection strategies.

Traditional sources of data are currently limited, expensive and do not normally have the outreach to the most vulnerable. New, innovative sources of data need to be explored to create a much more comprehensive and meaningful set of statistics that are technically feasible, politically acceptable and obtain stakeholder ownership. Smartphones, satellite imagery, social media, and the ‘Internet of Things’ continuously generate data everywhere faster and more detailed than ever before. These technologies offer new measurement opportunities and challenges for the land sector. However, their success is dependent upon convincing citizens to trust these solutions and understand the benefits of participation.

Need for Core Set of Land Indicators

Over the past decade, the global land community has seen a growth in consensus that land tenure security for all and equitable land governance are foundations for sustainable economic development and the elimination of poverty. This consensus is reflected in the VGGTs (FAO 2012) and in other related regional and global instruments such as the Framework and Guidelines on land policy in Africa (LPI 2011). The international donor community has also paid renewed attention to land governance in response to the new wave of private land acquisition and land-based investment in the global south (GLII 2015).

To date, development agencies and programmes for land-related interventions have established their own systems for monitoring outcomes; there is no overall comparability of progress in different countries or the effectiveness of different approaches. Monitoring has also tended to focus on land policy and legislative processes and on performance of individual projects rather than on people’s perceptions of tenure security and the development outcomes of land governance systems as a whole. In addition, there are large gaps in available data, including baseline conditions, and coverage of national land information systems. However, an initial Conceptual Framework for the Development of Global Land Indicators has been formulated (GLII 2015).

Traditional Sources of Land Indicators

The current, principle data sources available (UN Habitat / GLTN 2014) to support comparable global reporting, include:

- Administrative data, in particular that derived from national land information systems, although in many countries these datasets are incomplete (only 30% of the world’s population is included) and not up to date, or gender-disaggregated, and therefore requiring supplementation from other data sources;

- National censuses and household surveys, for which there is considerable scope for expansion by introduction of specific land-related modules into existing national surveys, designed and adapted so as to elicit consistent data across different countries;

- Purpose designed global polls, comprehensive sample surveys managed on a global basis to supplement data available nationally on questions not easily integrated into demographic and household surveys, for example, perceptions of tenure security for which a “perception module” is under development by the World Bank; and

- Expert assessment panels and expert surveys, which provide important ways of assessing the quality of legal frameworks, qualitative improvements and changes, and of making sense of institutional processes and complex and incomplete datasets from different sources.

Data collection of globally comparable data will require significant investment in additional datasets and capacity.

Innovative New Approaches

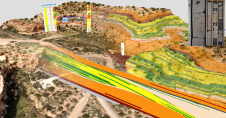

A number of new, innovative approaches to land administration are appearing that will accelerate the coverage of security of tenure and extend the formal data sources available to support global indicators. New approaches have recently been tested in countries such as Rwanda, Ethiopia, in the Europe and Central Asia region, in the South East Asia region, and in the 1990s in many Eastern European Countries. Experiences in these countries have helped form the fit-for-purpose (FFP) approach to land administration. Rwanda provides one of the best examples, where a nationwide systematic land registration started after piloting in 2009 and was completed in only four years.

The FFP approach to land administration has emerged as an enabler, accelerator and game changer. It offers a promising, practical solution to provide security of tenure for all and to control the use of all land. UN-HABITAT Global Land Tool Network (GLTN) has recently released a reference document “Fit-For-Purpose Land Administration Guiding Principles,” (Enemark et al, 2015).

A good example of innovative use of new technology to accelerate security of tenure is the USAID Mobile Applications to Secure Tenure (MAST) project in Tanzania (USAID 2015). USAID has completed an innovative pilot that utilised an easy-to-use, open-source mobile application that can capture information to issue formal documentation of land rights. Coupled with a cloud-based data management system, the project is designed to lower costs and time involved in registering land rights and, importantly, to make the process more transparent and accessible to local people.

The project was implemented in rural Tanzania working directly with villagers (trusted intermediaries) to map and record individual land rights, strengthen local governance institutions, and build government capacity. The Ministry of Lands then had the information necessary to issue MAST beneficiaries with official Certificates of Customary Right of Occupancy.

A key feature of these citizen-centric approaches is the use of a network of locally trained land officers acting as trusted intermediaries and working with communities to support the identification and adjudication process. This approach builds trust with the communities and allows the process to be highly scalable. The training, support and supervision of these local land officers requires new strong partnerships to be forged with land profession associations, NGOs, CSOs and the private sector. Over time, the trusted intermediaries will most likely self-organize into collaborating networks and resources may be shared with other information services, e.g. health and agriculture.

The UN Secretary General has proposed that the framework for monitoring progress towards the SDGs should take full advantage of the data revolution.

Crowd-sourcing Evidence of Land and Resource Rights

The range of devices in the mobile ecosystem, such as tablets, cameras, GNSS, mobile remote sensing / photogrammetry and mobile power, are enabling citizens or trusted intermediaries to directly capture evidence of land rights (McLaren 2011). An increasing number of crowd-sourcing initiatives are emerging to provide increased security of tenure to vulnerable communities.

- Rights Resources Initiative (RRI) – RRI’s forest tenure database is an interactive tool to compare changes in legal forest ownership from 2002 to 2013 between countries, regions, and lower- and middle-income countries. The quantitative approach monitors spatial forest tenure data. This statutory forest dataset currently covers 52 countries containing nearly 90% of the world’s forests. Much of the information is crowd-sourced. (rightsandresources.org/en/resources/tenure-data/tenure-data-tool/)

- Rainforest Foundation UK - The “Mapping for Rights” programme has been active in the Democratic Republic of Congo. It trains forest people to map their land using GPS devices. The information captured is used to create a definitive map of the land used by semi-nomadic communities, which can be used to challenge decisions that see them excluded from areas of forest (http://ictupdate.cta.int/ en/Feature-Articles/Crowdsourced-land-rights/%2869%29/1353928539).

- Open Tenure (SOLA) - Open Tenure supports a crowd-sourcing approach to the collection of tenure-related details by communities. (fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/nr/land_tenure/OPEN_TENURE.pdf).

- Landmapp – Landmapp is a mobile platform that provides smallholder farmer families with documentation of their land. They also provide them with a profile which they can access technical and financial services that are precisely tailored to their circumstances (www.landmapp.net).

- Cadasta Foundation – Implementing a global platform to manage crowd-sourced land rights information is due for release in 2016 and could provide a common platform for all the currently discrete land rights initiatives to manage evidence of land rights and create transparency and publicity (http://cadasta.org).

- STDM - A pro-poor, gender responsive and participatory land information model recognising the need for legal pluralism and a broader set of person-land relationships found in legitimate tenure types. GLTN have also produced a STDM solution, based on QGIS, that manages land rights data in the STDM model (stdm.gltn.net/).

Potential New Innovative Sources of Land Information

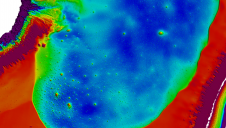

A number of innovative approaches are emerging to remotely derive land information such as crowd-sourcing information from satellite imagery. DigitalGlobe’s Tomnod platform (www.tomnod.com) uses Artificial Intelligence (AI) powered by crowd-sourcing to automatically identify features of interest in satellite and aerial imagery. Tomnod runs crowd-sourcing campaigns that attract thousands of volunteers around the globe. One campaign is mapping populations across Ethiopia.

Facebook has recently used its AI tools to identify human-made structures in 20 countries across Africa. This involved analysing 14.6 billion satellite images and has resulted in 350Tb of data with a spatial resolution of 5m. This informs Facebook’s Internet.org initiative.

The location of mobile phones carried by members of a community can be passively monitored over a period of time to track movements across their territory. Overtime, the extent of these recorded tracks will define the boundaries of their land and resource rights.

The increasingly pervasive mobile phone in developing countries provides opportunities for obtaining data on citizens’ / communities’ perception of tenure insecurity. The results would then be used to plan and target security of tenure programmes globally.

Extending community mapping initiatives could increase engagement with communities. A significant number of such initiatives are being activated across the globe. Examples include:

- The Extreme Citizen Science (ExCiteS) research group at UCL are recording community resources with forest villages (described at www.scidev.net/global/indigenous/multimedia/mapping-the-congo.html). This could be extended to ask the anthropologists who are working in the field to talk about perceptions of ownership and land use.

- The OpenDRI initiative of the World Bank involves extensive OSM mapping with a focus on disaster preparedness. A good example is in Kathmandu, Nepal (www.youtube.com/watch?v=L2IFYJigcQs). Specific mapping sessions with OSM could include collections of perception data.

Another source could be local radio communication campaigns designed with facilities for citizens to leave voice messages or SMS responses. The deciphering and geo-referencing of the messages could be crowd-sourced.

The evolving capabilities of Big Data and big analyses may prove to be another effective way of deriving perceptions of insecurity of tenure across communities and regions. The use of datasets such as property valuations, micro-financing, mortgages, addresses, business registers, school registers, census, marketing campaigns, social security payments, property tax, agricultural grants, mobile phone users. . . could all be used to model, analyse and derive perceptions of insecurity of tenure, especially when many of the datasets are georeferenced.

Another option might include an approach similar to the UNICEF uReport outreach to youth in Uganda. This is a free SMS-based system that allows young Ugandans to speak out on what’s happening in communities across the country, and work together with other community leaders for positive change. A further option might use established trusted intermediaries that are currently contributing to other information services, such as health and agricultural services, to extend their reporting to land issues.

Another possibility would be to use SMS based surveys can be arranged through mobile service providers, globally. For example, Geopoll (http://research.geopoll.com/) is the world’s largest mobile survey platform, with a database of 200 million users in Africa and Asia. The approximate cost is around $5 / completed survey.

The increasing use of social media (Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, WhatsApp…) across the globe (Facebook has over 1.6 billion users) provides excellent opportunities to tap into these communication channels and forums to derive information on the perception of insecurity of tenure.

Conclusions

Many of these new sources and channels for capturing evidence of land rights and indicators, such as perceptions of insecurity of tenure, are already delivering successful projects. However, there are several key issues to be investigated, understood and resolved before the approaches can be widely accepted and can go to scale:

- What are the technological limits and opportunities?

- How and where is this crowd-sourced data stored, quality assured and accessed to allow communities to police their data collection efforts?

- How can engagement be maximised and can campaigns be promoted across communities? What motivates communities to participate? What is required to make crowd-sourcing go to scale?

- How is this information used in decision making? Where are those decisions made, and how do such projects improve the quality of decision-making and community participation? More broadly, what are the socio-technical issues and how does the technology disrupt power relationships within and outside the community?

- How will citizens be convinced to trust these solutions and understand the benefits of participation? How will privacy and security of information be managed effectively to provide the necessary security of these sensitive sources of land rights information?

These new innovative sources of data need to be explored to quickly create a much more comprehensive and meaningful set of statistics that can provide an insight into the size of the security of tenure gap and help plan priorities for its reduction.

This article was published in Geomatics World July/August 2016

Value staying current with geomatics?

Stay on the map with our expertly curated newsletters.

We provide educational insights, industry updates, and inspiring stories to help you learn, grow, and reach your full potential in your field. Don't miss out - subscribe today and ensure you're always informed, educated, and inspired.

Choose your newsletter(s)