Map Database Updating in an SDI

| UAVs increasingly used for rapid image capture. |

One of the more rewarding aspects of my day job is teaching undergraduate students. Many of the challenges that my classmates and I faced when we graduated are fundamentally different from those faced by graduates nowadays. We were involved in creating the comprehensive control frameworks, and digital topographic and cadastral databases in place today. My students, on the other hand, already work in data-rich environments. With multiple spatial data infrastructures (SDI) in place, today’s graduates must make informed choices regarding which types of existing data they will employ in their solutions. Only then can they determine what they need to add through further data collection.

This is an important project design challenge. Going into the field to collect new data may ensure you know the quality of your own data, but it is not always the most cost-effective solution.

Today, public and private mapping organisations face the same challenge. With their respective SDIs in place, a typical mapping programme – be it, for example, in Natural Resources Canada, the USGS, the UK’s Ordnance Survey, TomTom or Google – can now make use of an imposing array of options for detecting and mapping changes. As technologies advance, new options appear and old ones diminish.

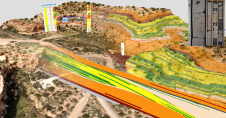

Let’s start organising those options. At the highest level, the choice is between complete or incremental revision. Should you replace your base or only update it on a patch- or feature-basis in areas where changes occur? If opting for incremental updating, consider the institutional options that are open to you in terms of change-detection and map-updating operations: in-house production, project- or programme-based contractors, external custodians offering updates to particular data types, and even individual volunteer suppliers. Most programmes today use some combination of these.

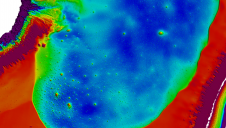

If considering in-house or contract production, a quick look at past GIM International articles offers a wealth of alternatives: soft copy photogrammetry, interpretation and on-screen digitising of orthorectified high-resolution vertical imagery, interactive and automatic extraction of buildings and roads, and ground surveys. There are even choices to be made about how we obtain and deal with the imagery. Sources of rectified high-resolution vertical imagery include satellites, commercial mapping aircraft, and unmanned airborne vehicles. Georeferenced horizontal and oblique digital images may now be obtained from vehicle-based mobile mapping systems, handheld cameras, and even smartphones.

I’m curious. How many channels of input to their change-detection and database-updating operations does a typical mapping organisation employ today? At what number does the whole process become too confusing or even unmanageable? Is there an optimum number of channels to consider? We’re just getting started – watch this space for more!

Value staying current with geomatics?

Stay on the map with our expertly curated newsletters.

We provide educational insights, industry updates, and inspiring stories to help you learn, grow, and reach your full potential in your field. Don't miss out - subscribe today and ensure you're always informed, educated, and inspired.

Choose your newsletter(s)