Who Wants to be a Surveyor?

This article was originally published in Geomatics World.

GW Technical Editor Richard Groom presents a personal view, with contributions from others, of issues surrounding the promotion, education and training of surveyors. A particular problem he identifies for the profession is that of the part-time surveyor.

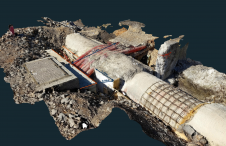

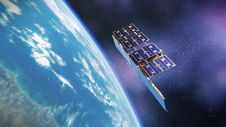

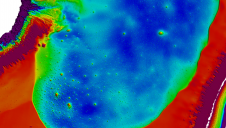

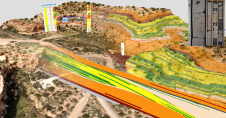

Thanks to technology, we are now able to survey more detail, faster and more cheaply than ever before. The surveying profession has expanded well beyond its origins in ‘Land’ to encompass ‘Geospatial’ and ‘Spatial’. If it’s physical we can measure it in 2D, 3D, 4D and more. It’s an exciting world, above and below water, made even more stimulating by our ability to model the data that we survey, to analyse and display its attributes, bring it to life (through visualisation), show how objects change and most importantly, compute the hard figures needed to optimise designs.

It’s a world which should enthuse young people and have them clamouring to join in, but sadly this is not the case. Universities cannot attract the best students and employers complain that there are not enough potential employees of the right calibre in the market place.

We can think of education and training as taking place on three levels:

- Education of the general public

- Education and training of technicians

- Education of professionals

Educating the Public

This article concentrates on promotion of the industry to the general public. This is high-level education for people who should know enough about our industry to decide whether they want to join it and if they don’t, who we are and what we do.

A higher general awareness of geomatics as a profession would trickle down to more and more suitable candidates for technician and professional education and training, and consequently, better recognition for those who are qualified to practice. In Britain, one has to admit that, for various reasons, including the fragmented nature of our profession, there has been very little effort in this regard. This is reflected in the haphazard way in which many of us enter the profession.

Technical Education and Training

At technician level, the lack of government-sponsored courses has resulted in The Survey Association setting up the Survey School in Worcester and recently in taking over ownership. The school meets the needs of the surveying companies and its qualifications are recognised by the industry.

The surveying and mapping industry has expanded beyond belief over the past thirty years. On the mapping side, CAD and GIS have provided the impetus. On the surveying side, it has been new, better and faster data collection, processing and presentation tools. In general, this is accompanied by easier operation, although one could argue that a Wild T2 was easier to operate than a high-end total station.

Perhaps GIS demonstrates most clearly what has happened. It used to be the preserve of a few highly paid specialists who understood the theory and were able to work large, slow and temperamental programs. GIS is now used by millions to carry out simple queries but only a few understand it thoroughly and are able to provide advice for the design and implementation of systems. In other words, there are a great many GIS users with skills gained through training and very few GIS professionals.

We live in a push-button world, but surveyors bring to that world qualities that make the best of the amazing technology that is available. As John Hallett-Jones of Glanville Geomatics says: “There is one aspect (of technical training) that is never talked about and that is the value of experience and the ability to have an ‘eye for the ground’, to take reality and to best represent that in the most efficient communicative way. We find that this aspect takes a good deal of nurturing with new employees and is a priceless attribute to have, but is often overlooked.”

Part-time Surveyors

Does current geomatics education and training reflect this new reality? It does, in the sense that the opportunities for appropriate education and training are there. But whether surveyors actually follow them is another matter and that is largely down to perceptions of our profession by others and indeed by our own perceptions. In Britain, many people carry out surveying work and most of them probably do not have surveying qualifications. Indeed, for many, I suspect they (or their bosses) believe that there is little more needed than to buy the kit and follow the quick-start manual. There is no doubt that field surveying has been ‘de-skilled’ over the years, but every survey should follow principles that will assure its quality. The public at large (and fellow professionals who should know better) can see the field equipment in operation and it looks easy, but they do not see the planning that goes on before the survey, or the data processing and analysis that follows in the office, and these are still very much skilled activities.

These part-time surveyors are usually technicians or professionals from other disciplines carrying out surveying at a technical level. They use surveying tools for particular purposes and see no need for training beyond, by analogy, the expertise they would need to use MS Word to write a report. Many do not see a need to learn the basic principles of surveying – and possibly don’t even recognise that there are any.

From a client’s point of view, what constitutes adequate education and training for this group of technicians? If they come from a civil engineering background they probably receive some surveying education and training as part of their civil engineering course, but is it fit for purpose? Would surveyors consider that the lecturers are competent to convey ‘the surveying body of knowledge’ to their students? Anecdotal evidence suggests that this question needs addressing. If the surveying module in non-surveying courses is taught to a shallow level by poorly qualified lecturers focusing primarily on the array of technology available, the students will see ‘specialist’ surveyors as experts in the trivial, which is wholly damaging to us.

When part-time surveyors enter the world of work, or are called upon to do ‘some survey work’, how do they learn to select and use the right equipment for the job, process, report and manage the results? Surveyors (or rather, their clients) should be crying out for modular structured training, with associated education, that includes meaningful certification of courses (and certification for graduates), and those modules should build towards a chartered qualification. Also, clients should value certification: the benefit of being able to recognise ‘good’, as an assurance of competent work. As Graham Mills of Technics says “Certification through a recognised body would help to raise the bar.”

The Surveying Consultant

Unfortunately, part-time surveyors also tend to act as the client’s agent, when commissioning larger projects. When working in an advisory and supervisory capacity they should, at least, be intelligent clients, which arguably means that they are working in the third of the categories listed at the beginning of this article. They are doing consultancy work, potentially demanding a much deeper understanding of geomatics, which they seldom possess, or just as importantly, sufficient understanding to know the bounds of their knowledge and when they need to hire a consultant. In large organisations, this is work that should be carried out, or at least overseen, by qualified professional surveyors.

But local and national government departments, consulting engineering and architectural practices, almost without exception, do not employ a single professional surveyor in this capacity and neither do they employ external consultant surveyors to advise. Surveying, they appear to believe, is a technician’s job which can be managed by the people who will use the data. Some are competent, but many are not. The less competent, when faced with a tender evaluation will make their judgement based upon ignorance, or the parts of the tender that they do understand – like Health and Safety – with the result that they promote the ‘race to the bottom’ by failing to weed out technically inadequate submissions and failing to accept the best value bid that meets the requirements of the job. When it all goes wrong, you can bet that it will be the contractor’s, or the profession’s fault. Perhaps surveyor licensing is the answer, but surely we can achieve a better result through adequate education, training and regulation.

Most surveying work is required to support projects and another frequent hindrance to good surveying is the current passion for ‘project management’: an activity which is the preserve of generalists who, as Chris Preston, RICS Geomatics Professional Group Chair, says, “know a little about a lot of things but not too much about anything! Unfortunately, that ‘anything’ usually does not include surveying, geomatics or associated fields. It is purely about delivering a project to budget, on time and hopefully what was needed. Geospatial engineering is now considered very specialised and those who do the actual data collecting, lowly skilled.”

The challenge for surveyors is to express the value of their work, because this frequently manifests as ‘savings’ or as risk mitigation, to which the client could well be blind or sceptical, whereas he can see the costs without any help. Also, those benefits and savings arise over the lifetime of assets rather than of projects, which is therefore beyond the deliberately blinkered view of the project manager. BIM looks at lifecycle asset management, so it should help to overcome the short-term mentality, but it is still more likely that individual phases of the BIM lifecycle will be managed as individual projects and that the long-term benefits of the survey will be overlooked.

Are We Powerless?

We appear powerless to break this prejudice. However, there are very few organisations that do employ professional surveyors to oversee their geospatial activities. Their role is to advise within the organisation, ensure that surveying is fit for purpose and provides value for money, maintain the surveying infrastructure and manage and archive surveying data. The success that they achieve is largely down to just ‘being there’ and therefore being in a position to influence, even if only at the lower levels of the organisation. They have to cultivate champions to survive, usually with no support from the profession and yet their presence is crucial to the health of the industry as a whole.

Promoting the Profession

So, what are we doing to promote our profession in Britain? Ten years ago, Newcastle University established a website – www.geomatics.org.uk which was excellent for its time and well received, but it relied upon support from industry bodies as well as a hefty grant and is now no longer operating. The professional institutions have websites which give descriptions of the profession. The RICS has recently taken substantial adverts in The Guardian, but one has to question whether the audience of prospective geomatics surveyors reads that paper.

There are occasional TV programmes that feature surveying in some form or other. For example, surveying has played a bit-part in Time Team, there was a fascinating programme featuring survey control surveying in the Andes a few years ago, and more recently the use of LiDAR was used to uncover the mysteries of Angkor, in Cambodia. The latter did not mention surveying or geomatics – just the technology, thus reinforcing the unhelpful notion that the tools are paramount. Of more relevance to 8-15-year-olds is Minecraft. It introduces the concepts of mapping and to some degree design and engineering through the gaming environment. Perhaps there is a way to use this to help promote our profession. To read more about this link see the August issue of our sister title GIS Professional.

In Britain, there is a recent initiative to promote construction in schools. Class of Your Own (COYO) is a British charity aiming to dispel the negative image of construction as a career path. Surveying is included within the scope of COYO but therein lies another problem: the perception that surveying is just a service to engineering and construction. Whilst COYO is a commendable idea, it does nothing to tackle the surveyors’ identity crisis and promote the distinctive qualities that surveyors offer. Stemnet (Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics Network www.stemnet.org.uk) is an organisation with a similar role to COYO but with a more general remit. A unique aspect of its strategy is STEM Ambassadors. There are 27,000 volunteer ambassadors who act as role models and promote STEM subjects to young learners. Stemnet also has a STEM Clubs Programme, which provides free, impartial, expert advice and support to schools that want to set up or develop a STEM Club. The clubs are a fun and rewarding way to boost enjoyment and learning across STEM, outside the classroom.

The geomatics skills shortage is not just a problem in Britain. A European project – GeoSkills (http://www.geoskillsplus.eu/) aims to identify and set up optimal ways to Raise Awareness of GEO studies and increase student enrolment in the EU. The Netherlands is also having difficulty attracting young people into surveying. That country’s solution was to club together to produce a very impressive video: http://geo-pickmeup.com/ why-we-need-geographers-the-go-geo-campaign/

Surveying Spectaculars

Several years ago, in New South Wales, Australia the problem was approached from several angles, as described by Roberts and Iredale in GW Jan/Feb 2011. They reported that work experience placements can be useful, provided that the company offering the placement is wholehearted about it, otherwise it can be a destructive experience not just for the student but also for the industry – bad news travels even more rapidly than good news. In Britain, work experience placements are offered to children at age 15/16 and generally too often arranged by the student’s parents. Three organisations in New South Wales clubbed together to produce a successful DVD. They also arranged ‘Surveying Spectaculars’ otherwise known as ‘Maths in Surveying Days’ in schools and formed links with the state-wide association of careers advisors – perhaps the most valuable means of connecting limited surveying resources with the maximum number of students. They have also worked with the NSW department of education to put surveying examples in the mathematics curriculum and with the author of a textbook with the same objective in mind. Frequently school students see topics like geometry as completely irrelevant, yet geometry is pivotal to geomatics and some surveying involvement could be highly motivational.

Identify the problem

In the course of writing this article, it has become clear to the writer that we should target our efforts in two directions, firstly towards the public at large, particularly at school age and secondly towards the professional advisors from other disciplines who hold such sway over our industry and can cause it such damage.

Co-operation is the key

A feature of the Australian experience is that they could only muster the resources needed through the co-operation of several professional bodies. When it comes to high-level promotion of the industry, that co-operation could extend across all the geospatial disciplines, including GIS and cartography through, for example, UK GeoForum or the kind of co-operation that resulted in GeoBusiness. Funding should come from the institutions, which means pushing the subject higher up the agenda and perhaps that could be supplemented by crowdfunding contributions for a specific project?

Acknowledgements

Contributions gratefully acknowledged from Mike Coward, John Hallett-Jones, Graham Mills, Chris Preston and the GW Editorial Board members.

This article was published in Geomatics World November/December 2014

Value staying current with geomatics?

Stay on the map with our expertly curated newsletters.

We provide educational insights, industry updates, and inspiring stories to help you learn, grow, and reach your full potential in your field. Don't miss out - subscribe today and ensure you're always informed, educated, and inspired.

Choose your newsletter(s)